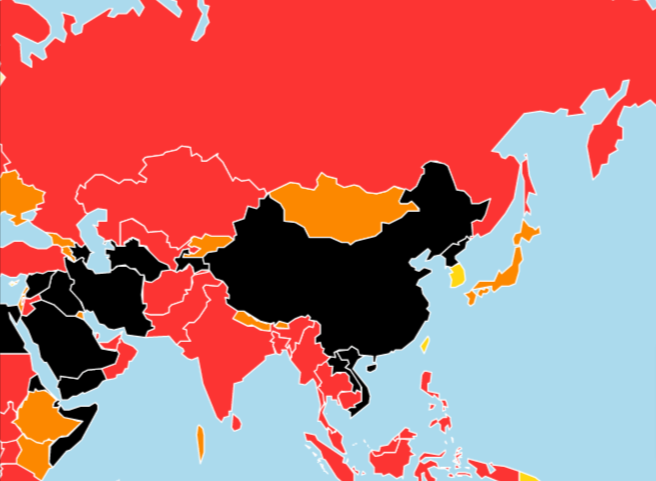

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) have released their latest rankings on the World Press Freedom Index. Published every year since 2002, the Index ranks 180 countries and regions according to the level of freedom available to journalists.

With 34 countries and more than half the world’s population, the Asia-Pacific region holds all the records, with the world’s biggest prisons for journalists and bloggers, especially China and Vietnam, and the world’s deadliest countries for journalists and bloggers, above all Afghanistan, Pakistan, Philippines and Bangladesh.

The region’s authoritarian regimes have used the Covid-19 pandemic to perfect their methods of totalitarian control of information, while the “dictatorial democracies” have used it as a pretext for imposing especially repressive legislation with provisions combining propaganda and suppression of dissent. The behaviour of the region’s few real democracies have meanwhile shown that journalistic freedom is the best antidote to disinformation.

China continued to rank at 177 out of 180 countries, unchanged from last year. The Chinese authorities have tightened their grip on news and information even more since the emergence of Covid-19. Seven journalists are still being held for their coverage of the pandemic and more than 450 social media users were briefly arrested for sharing “false rumours” about the virus. In 2021, China continues to be the world’s biggest jailer of press freedom defenders, with more than 120 currently detained, often in conditions that pose a threat to their lives.

North Korea, up 1 at 179th, continues to rank among the Index’s worst performers because of its totalitarian control over information and its population.

Singapore, down 2 at 160, is always quick to sue critical journalists, apply pressure to make them unemployable, or even force them to leave the country. The political control is coupled with an economic straitjacket. The red lines imposed by the authorities, known by Singapore’s journalists as “OB markers” (for out-of-bounds markers), apply to an ever-wider range of issues and public figures. The authorities have also started sending journalists emails threatening them with up to 20 years in prison if they don’t remove annoying articles and fall into line.

In Myanmar, down 1 at 140th, Aung San Suu Kyi’s civilian government used the pretext of combatting “fake news” during the pandemic to suddenly block 221 websites, including many leading news sites, in April 2020. The military’s constant harassment of journalists trying to cover the various ethnic conflicts also contributed to the country’s fall in the Index. The press freedom situation has worsened dramatically since the military coup in February 2021, with media closures, mass arrests of journalists and prior censorship.

The semi-autonomous “special administrative region” of Hong Kong maintains its position at 80 from last year, but the national security law that the Chinese government adopted in June 2020, allowing it to intervene directly in Hong Kong in order to arbitrarily punish what it regards as “crimes against the state,” is especially dangerous for journalists. Nonetheless, there is resistance. It is being led by a handful of independent online media such as Citizen News, Stand News, The Initium, Hong Kong Free Press and inMedia. They exist thanks to participative funding and their audience is growing.

Vietnam remained at 175, and reinforced its control of social media content, while conducting a wave of arrests of leading independent journalists in the run-up to the Communist Party’s five-yearly congress in January 2021.

Thailand, up 3 at 137th, Philippines, down 2 at 138th, Indonesia, up 6 at 113th and Cambodia at 144th, adopted extremely draconian laws or decrees in the spring of 2020 criminalising any criticism of the government’s actions and, in some cases, making the publication or broadcasting of “false” information punishable by several years in prison.

Malaysia, down 18 at 119th, recorded the biggest fall of any country in the Index. The fall is directly linked to the formation of a new coalition government in March 2020 which adopted a so-called “anti-fake news” decree enabling the authorities to impose their own version of the truth.

In Pakistan, which remains 145th, the all-powerful military intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), continues to make extensive use of judicial harassment, intimidation, abduction and torture to silence critics both domestically and abroad. But the Pakistani censorship apparatus is still struggling to control social media, the only space where a few critical voices can be heard.

India also remains at the same position as last year, 142nd. With four journalists killed in connection with their work in 2020, it is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists trying to do their job properly. While the pro-government media pump out a form of propaganda, journalists who dare to criticise the government are branded as “anti-state,” “anti-national” or even “pro-terrorist” by supporters of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). This exposes them to public condemnation in the form of extremely violent social media hate campaigns that include calls for them to be killed, especially if they are women. When out reporting in the field, they are physically attacked by BJP activists, often with the complicity of the police. And finally, they are also subjected to criminal prosecutions.

Independent journalism is also being fiercely suppressed in Bangladesh, down 1 at 152nd, Sri Lanka at 127th and Nepal, up 6 at 106th – the latter’s rise in the Index being due more to falls by other countries than to any real improvement in media freedom.

A new prime minister in Japan, down 1 at 67th, has not changed the climate of mistrust towards journalists that is encouraged by the nationalist right, nor has it ended the self-censorship that is still widespread in the media.

The Asia-Pacific region’s young democracies, such as Bhutan, up 2 at 65th, Mongolia, up 5 at 68th and Timor-Leste, up 7 at 71st, have resisted the temptations of pandemic-linked absolute information control fairly well, thanks to media that have been able to assert their independence vis-à-vis the executive, legislature and judiciary.

You can see all the rankings and details on the press freedom map, which offers a visual overview of the situation in each country and region in the Index. The colour categories are assigned as follows: good (white), fairly good (yellow), problematic (orange), bad (red) and very bad (black).

Subscribe to the radioinfo podcast on these platforms: Acast, Apple iTunes Podcasts, Podtail, Spotify, Google Podcasts, TuneIn, or wherever you get your podcasts.